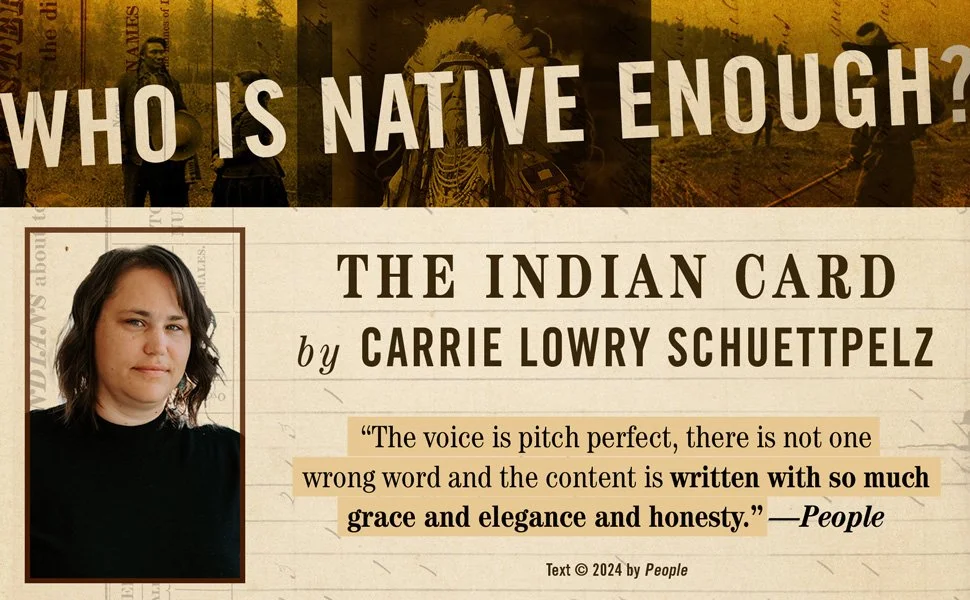

Check out our Book Club Discussion Guide for The Indian Card: Who Gets to Be Native in America by Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz

The Indian Card gifts the reader with so much! It is unflinching in its accounting of history and the many wrongs committed by the U.S. Government, but it is also the intensely readable story of one scholar and researcher who set out to explore the process of Tribal enrollment for herself and her two children after the author realized her “Indian card” had expired. Each chapter also features stories and interviews with Native and Indigenous individuals from all over the country that the author met while exploring her own identity and the question of who really gets to be Native in America.

Discussion Questions for The Indian Card: Who Gets to Be Native in America by Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz

Membership - What did you know about the Indigenous Nations and Native American Tribes based in the United States before reading The Indian Card? Did you know anything about the Tribal enrollment process?

Belonging - The author’s Lumbee relatives live in close proximity. How does your family celebrate belonging? Has colonization impacted your family life? Why or why not?

Counting - When recounting the history of census taking, the author quotes historical anthropologist Jane Ferguson (65) who explains that, historically, institutions who take censuses are "rooted in imperialism." Why do we take a census in the United States? Have the results always been collected fairly and accurately? How has census data been used for harm?

Payment - Between the 1778 Treaty with Delaware and the 1871 appropriations bill, 369 treaties were ratified. Despite many historical records, the terms used by many scholars to describe the history between the U.S. government and Native American Tribes are dehumanizing (removal, assimilation, reorganization...) and historical accounts are kept to brief summaries in most history books. What is something you learned about the history of the interactions between the U.S. Government and Native American Tribes from reading The Indian Card? What humanizing words would you use to describe this period of history?

Remove - "The events surrounding President Andrew Jackson's passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 are a master class of gaslighting." (103) The implementation of this act, which Jackson claimed was favorable to Native people could be described as genocide or ethnic cleansing. For example, one in four Cherokee people died during their forced eight-month journey. Most of the 5,000 mile journey was walked on foot, which is an average of twenty miles per day. Native people were placed in animal pens, marched across ice and snow without proper clothing or shoes, given limited breaks, and fed bad food. The soldiers escorting them were well equipped and no record exists of a soldier dying. Why was the label "Indians About to Emigrate West of the Mississippi" used for the muster roll records? Why is Andrew Jackson (still) on the $20 bill in the U.S.?

Separate - "...largely, land has been (and continues to be) at the forefront of so much of American History that it would be a mistake not to emphasize its importance. It would also be a mistake not to acknowledge that a major story from the last several centuries of Native America has been about stolen land." (page 130) What was the purpose of the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) in 1887? What resulted from passing the Dawes Act and the Curtis Act? Do you have a better understanding of the #LandBack movement after reading this book?

Disconnect - The Indian Reorganization Act (1934) was an attempt to right some of the wrongs committed by the U.S. Government by allowing Tribes self-governance and federal resources for health care and education on reservations. However, tribes who did not adopt a constitution approved by the Department of the Interior lost out on some of the financial benefits of the act (160). What is the lasting impact of many Tribes adopting constitutions with specific membership requirements?

Identity - The author’s former boss and mentor Jennifer Ho dislikes the tendency in public policy to embrace "false precision." (153) Were you familiar with CDIB (Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood) before reading this book? What is CDIB used for today? Have you ever been asked to quantify your identity?

Return - Around 170 of the 347 federally recognized Native American Tribes in the forty-eight contiguous United States use blood quantum as a part of the tribal enrollment process. Lack of "proof" of Indian blood also has prevented the Lumbee Tribe, of which the author is an enrolled member, from achieving "federally recognized status." Yet, more Americans seem to identify as Native than ever before with 9.7 million people—more than twice the census count in 2000—self-identifying as Native American or Alaska Native in 2020. As sovereign entities, the Tribes have the right to define their own membership. It is also important to acknowledge many alternatives are complicated. Do you think of the use of blood quantum functions more as a shield or a tool of extinction (as implied by scholar Mikaëla Adams on page 211) for the Tribes that use it? Can calculating blood quantum ever be separated from its racist roots in colonialism? What other actions could the U.S. Government take to right past wrongs and support Native American Tribes?

Dig Deeper: Unique Activity Ideas

November is also National Life Writing Month or Memoir Writing Month. The Indian Card originally started out as a memoir. Have you ever tried to write about your life? Carrie’s book is a wonderful example of how you may never know what will happen when you start telling your story. You might even want to get together with a group and write in a community atmosphere! If a published memoirist lives in your area, you could invite them to share a few tips over snacks before hosting a writing session for new memoir writers. Otherwise, the book Writing About Your Life is a great place to start.

Respectfully learn more about the culture of the Native American Tribe closest to you. Explore which Tribal Nation’s lands you may be on here. Many Tribes host events and classes open to the public. Another way to engage with Native American culture is to get together with a few friends and watch a documentary or try out a recipe from the First Nations Development Institute.

Host a Native Experiences Event celebrating the stories and artwork of Native and Indigenous people living in your community. Add a Human Library element to enhance the learning experience for attendees. You could even collect the art and stories shared into a book or recording that could be made available for the public to access at a local institution. You might even want to invite Carrie to speak about her experiences!

Gather your fellow spreadsheet lovers and start creating sheets about something you are passionate about in your community. Perhaps it is outlining the growing instructions for all of the native plants in your community or a directory of literary sights and businesses in your area.

Exclusive Author Interview with Carrie Lowry Schuettpelz

As a Midwesterner, do you have a favorite fall comfort food or autumn activity?

Carrie: I love the changing of the seasons, and fall is by far my favorite. We have a great pumpkin patch in our town, and we love taking our kids every year.

When did you start to feel that your research was evolving into something that could be a book?

Carrie: My process was actually the reverse — I began writing what I thought would be a memoir. The more I wrote, the more I realized that I needed to incorporate research into the story.

Your work involves conducting numerous interviews and extensive research. Can you share your process for organizing all that material? Do you have a particular system that works best for you?

Carrie: I'm not an outliner, but I do like having a rough sense of where things will go in the book. That being said, when I conducted the interviews, I didn't commit them to any one particular section. That seemed to happen organically. Overall, it made sense to me to write the book as a timeline, so the material came together that way.

What is the strangest thing you Googled while researching/writing this book? Or the strangest piece of research you discovered?

Carrie: I never thought I'd be looking into the Mongolian Empire, but there I was. I remember texting my agent and editor and saying, "You'll never guess what I'm writing about now."

Readers will soon learn you have a fondness for spreadsheets—tell us more! Do you have a spreadsheet you are most proud of? Is there a unique way you use spreadsheets that you swear by?

Carrie: My brain has always thought in terms of data and columns/rows. The spreadsheets I'm most proud of are those that are connected to action. Right now, my research assistants and I are working on quantifying individual treaties between Native Tribes and the U.S. federal government, in terms of the land stolen and how much money Tribes were paid for it.

Your book is such a candid and meaningful examination of what it means to be Native in the United States. What's one thought you hope readers will dwell on even after they have turned the last page?

Carrie: I hope we can begin to have more meaningful conversations about the real ways that federal policies have shaped not just identity, but things like land ownership, wealth, and financial equity — particularly for communities of color. And, I hope those conversations include ways we can take action to right the wrongs of history.

Are you working on any current projects you would like to share?

Carrie: I am the Director of the Native Policy Lab at the University of Iowa and right now we're working on a project to return Indian Boarding School records to survivors, their families, and their Tribes. The project actually stemmed from the work I did with Karen and Don Diver as part of my interviews for The Indian Card. We're currently working off a list of over 200,000 children whose records exist in the National Archives.